I was in a hurry. Five new admissions and a few consults the night before and just a few hours to see them all. As an attending physician on the family medicine residency inpatient team, I was supposed to meet with my team at nine for morning rounds.

One of the new consults on my list was from the orthopedic service.

“Alzheimer’s dementia, Right hip fracture. Assist with medical management of hypertension, diabetes, and dementia.”

“This should be quick.” I thought. I grabbed the patient’s chart to review. Quickly thumbing through it—ortho’s notes were cryptic and sketchy. Not much information. The nurses’ notes were more informative . . .

“93-year-old male with severe Alzheimer’s dementia. Non-communicative.”

I flipped to the back of the chart and noted a photocopy of the patient’s retired military ID card.

U.S. Air Force, Colonel, Retired

I went to see the patient. Entering his room, his 60-something-year-old son was at the bedside.

“Good morning, Colonel!” I called out from the doorway.

The old man weakly turned his head toward me and a smile came to his eyes and eventually across his lips.

He weakly responded in kind, acknowledging my rank (I was wearing my Air Force uniform). “Good morning, Colonel.” The visual cue of my uniform and me acknowledging his rank seemed to have penetrated the fog of dementia. For a brief moment you could see a spark in his eyes.

I asked a few doctor-type questions and the old man had no complaints. In fact, he didn’t respond at all. Just a blank stare. His son filled me in on the details of his medical conditions and recent fall.

I continued . . .

“So, Colonel, I assume you’re a World War 2 veteran. Can you tell me a little about your military service?”

He was slow and halting at first, fishing for words.

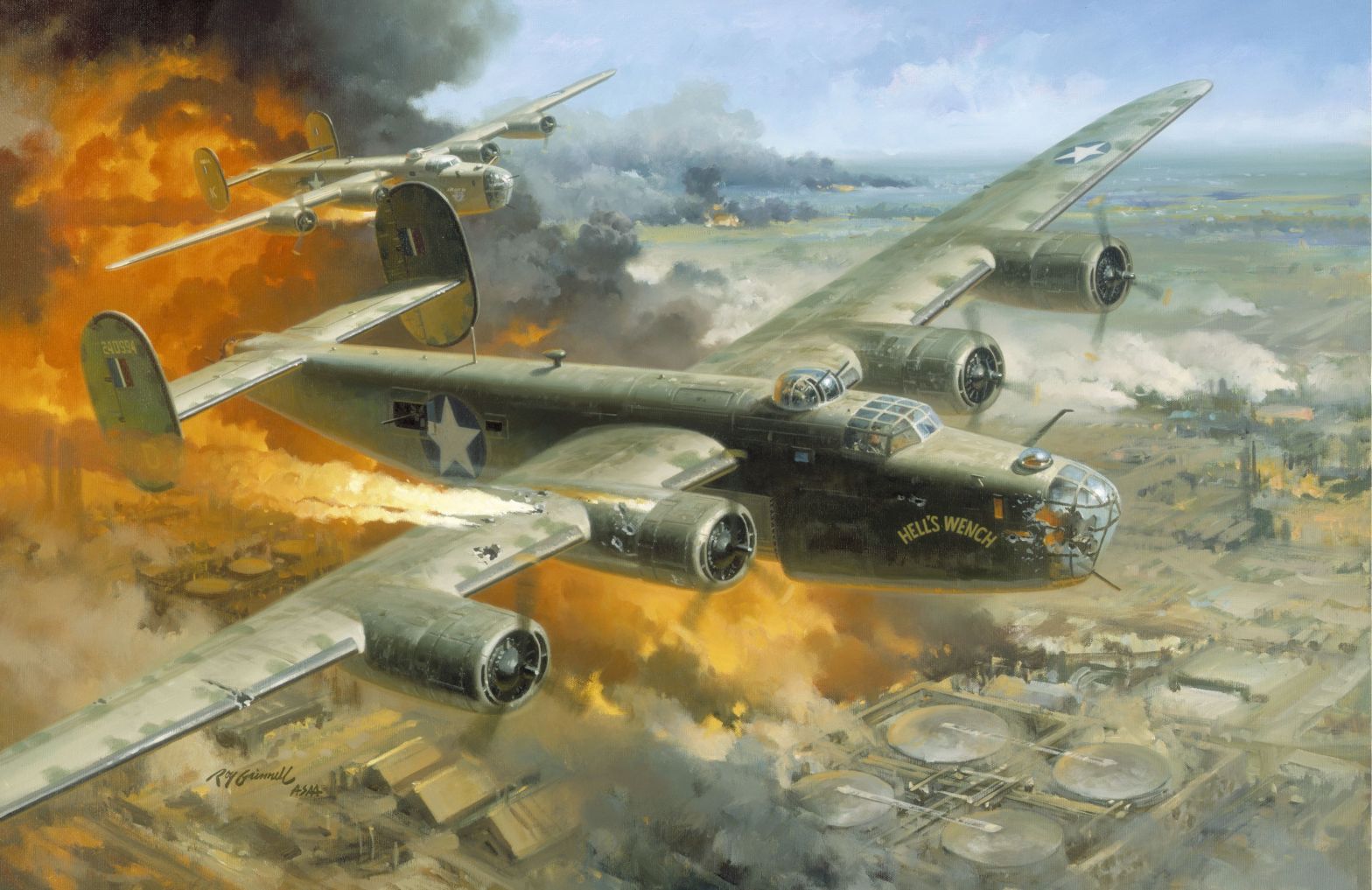

“Eighth Bomber Command”

“Pilot, B-24 Liberator”

“25 missions.”

The old man’s tempo, clarity and emotion increased and he began to tell his story. The descriptions were heartfelt and graphic. Bone-chilling temperatures. Lock-step flight formations. Flak so thick it was, as he described it, “almost like you could walk from plane to plane using the flak bursts as stepping stones.” And then there were the bravery, fear, and carnage. Crew members—his friends–injured, bleeding, crying, dying. Buddies who would be forever young, having paid the supreme sacrifice.

And the old man cried as if it all happened yesterday.

And then his son cried.

I cried too.

After 45 minutes of listening to the old man reminisce, I reluctantly excused myself to see my next patient. Now I was really running late. There was no way I’d be able to see everyone by 9:00 AM. Chasing me down the hall, the son caught up with me and grabbed me by the arm. I turned around.

“Thank you so much, doctor!” said the son, tearfully shaking my hand.

“For what?” I responded. ” I should be thanking you and your father. It was such an honor to hear your dad’s story!”

“No doctor, you don’t understand. You see, Dad never told us. His service in World War 2 was a secret he mostly kept from all of us. What happened this morning was such a gift to me,–for my whole family. I thought we had lost those memories forever.”

With great expectation, I went back for part 2 of the old colonel’s story the next morning but he had nothing more to say. Non-communicative. Back to baseline. He went back to the nursing home later that afternoon.

Everyone has a special story. I’m convinced of that. And those stories have the potential to enrich us in so many ways.

But we have to ask.

And we have to take time to listen.